Friday, December 13, 2013

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

Just When You Thought You'd Seen It All...Introducing Sparknotes: Bible.

They do have the basic gist, saying it is out to find the meaning of life, but they don't make many of our helpful connections or understand where it is coming from.They call the main character "the Teacher," which sounded kind of creepy to me. They then go on to explain a basic understanding of the Neheneh's, Amal's, Chacham's , and Yirei Elokim's philosophies, but because they lack the understanding of these "characters," they don' t see how this flows, and what each is trying to prove. Rather, they think this is just crazy ravings that make little sense and keep contradicting each other. The organization of ideas here is different, because the text is grouped into sections such as wisdom/ meaning in life, trends of human activity (life cycles, human emotion, cooperation), foolish actions and how to avoid them, and positive recommendations and reflections on life. This is summed up with an analysis on the book repeating how it is repetitive, contradictory, and nonsensical. "Hakol Hevel" is translated as "vanity of vanities," and they do reference the word hevel, translating it as "breath of the wind" and leading towards the interpretation of life being ephemeral.

Now, here comes the interesting part. Sparknotes states that Kohelet contrasts with the rest of the Old Testament because it questions receiving wisdom and ideals. They don't make the distinction here between Torah and Nach. They think these are just more "bible stories," and should be pondered and explained the same way. This, to me, is a pretty important distinction, and without it everything that can be gleaned from Kohelet is not the same. I think that, if they were aware of this difference, it would help them get more out of and have a deeper understanding of Kohelet. They also end on the note that a message of this book is that it is anti- "rigid or dogmatic wisdom." I didn't see this at all, but I think it might come from all the vague wording and metaphors. All in all, it's pretty interesting and worthwhile to check out! Here is a link : http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/oldtestament/section12.rhtml

Evil Ruins Everything

There is an idea in the Torah about how a youth's prayers are so much stronger than an adult's. Maybe it is because of this idea that the youth mean what they are saying when they pray because they don't see any evil in the world yet. But once you get older, and you are thanking G0d could it really be sincere because of all the evil that happens around you?

This concept, like Racheli's, links to what Charlie Harary talked about in one of his speeches. He talked about the idea that children who still haven't understood the world yet are the only ages that truly sincerely laugh at a joke or at something they think is funny. This can be the same type of concept as the one above. That they don't know their surroundings, and they are not aware of all the bad around them, so they don't have anything preventing them from laughing and having sincere fun.

The End of an Era

|

| We're never satisfied, are we? |

Kohelet is over, as you've probably heard, and I for one am not taking it that well. I'm pretty bummed out, feeling kind of sad. And being sad reminds me of having existential questions. And having existential questions reminds me of learning Kohelet... and then I'm reminded that we're not learning Kohelet. I think you get the point. Most of you guys did lovely jobs taking Kohelt into perspective and wrapping it all up on this lovely blog, so I'm not going to repeat any of you. Instead I will (you guessed it!) bring out some Calvin and Hobbes. Because I don't know when else I'll be able to so extensively blog about them. And that makes me sad. Oh, wait a second... I feel like we're just going around in circles- like this whole blog is cyclical. Is life, like this blog post, just one big cycle? Is it possible to make a difference in this blog, or in life? Oh, goodness!

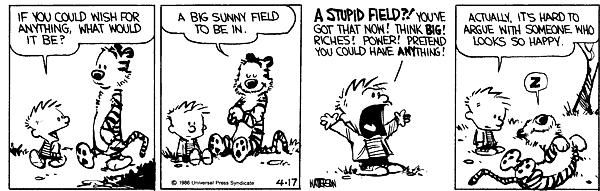

Right! Well, in no particular order, here are some Calvin & Hobbes comics that remind me of Kohelet.

To me, this brings to light the whole question of man's power over nature. How much control do we really have? We like to think we're the masters of the universe and that we control for everything, but, ultimately, we are brought to realize that no, we are not in control. There are factors we cannot account for. Unlike what the amal would like to believe, man can't fix everything. Which is okay, says the Yirei Elohim. We just need to recognize the hierarchy.

Mostly, this comic makes me happy. But I think we can relate it to Kohelet in the following way: oftentimes we are searching for happiness or meaning in the wrong places. We "wish" too high and get disappointed when our wishes aren't fulfilled. If we keep our heads on earth and are realistic about certain things in life, we can be happy individuals. If we are on the hunt for "big riches" and "power", we're not going to find meaning in our lives. Here are two other comics that echo the same ideas.

|

| Looking for meaning in the wrongs places... |

|

| I'd advise Calvin to give Kohelet a good read through and then reevaluate some of these thoughts. |

One of the other important things that Kohelet taught us is that finding happiness in ignorance is foolish. We must seek out answers and question. Even if we are unsatisfied with the answers we find and even if we don't find answers. Simply not thinking isn't really an option. It's in someways even "irresponsible", as Hobbes says, to live a life of ignorance. While learning Kohelet we grappled with some real difficult questions. Even though it was frustrating at times and I'm not completely pleased with all the answers, I'm glad that we spent the time discussing and delving on the hunt for answers and meaning.

This reminds this of the "ein chadash tachat hashemesh" refrain that we saw a lot at the beginning of the text. Sometimes it does feel like it's just "school, school, school," don't you think? It's important for us to recognize that every day is different. We should all try to "go for the gusto" in a way in our lives- you know, mix things up a bit- just to remind ourselves that every day is different and wonderful.

Sometimes we forget that believing in something means taking a leap of faith- putting faith in something that we can't see.

Why do you suppose we're here? Big question, huh? How do you think Kohelet would have answered this question?

Why do good things happen to bad people and why do bad things happen to good people! This was the turning point of the Nehaneh, and something the Chacham also struggled with. What they didn't realize was the two tiered system of justice that God has. But, you've got to give it to them- those are some hard questions. It's hard to have undying faith all the time when things like this are happening in your life.

Monday, December 9, 2013

Conclusion

I just wanted to share a few personal thoughts on the conclusion. Although we went through the whole Sefer from the perspective that the Amal, Yirei Elokim, Chacham, and the Nehene were all different characters.. when approaching it as if each is representative of a different side of Shlomo, it makes much more sense. When we look at Kohelet as an internal dialogue we can walk away with much more meaning. We can see each personality within Shlomo: wealth, wisdom, women, the BHMK. This give the יראי אלוקים depth.. it makes him more believable and gives him more credibility. Before I kind of thought that the יראי אלקים was pretentious and that he was making his philosophy seem much more easy than it is.. which really kind of angered me. It made me feel like: "what gives you the right to say that to me?" But instead, knowing that it's an approach that he came to on his own, that he wasn't just raised this way, it makes us more open to what he has to say. He had all of it, more physical experiences than we can imagine, money, power - yet he still comes to this conclusion: that recognizing that G-d's above us and we have accountability for our actions. This is what really gives his philosophy meaning, in my opinion.

I think it's really appropriate that we read this sefer on Sukkot. Sukkot is the Festival of Harvest - a time where we think we are in control (we grow our crops, water them, then harvest them.. where's G-d in that?). During Sukkot, we go outside and have a temporary home. We do this in order to show that we are not in control, that it's not about us, and that G-d is in control. This relates back to the Yirei Elokim's philosophy. It's a very appropriate message to the time, and gives us a lot to think about right at the beginning of the new year, a time in which many of us, especially myself, find it hard to stay connected and committed to all the things we promised at the beginning of the new year. We start slipping back into our normal life and Sukkot gives us an opportunity to rethink our goals and recommit ourselves. And most importantly, remind us that G-d is in control and that we are accountable for our actions.

Still searching for that meaning

The Yirei Elokim leaves us off with the following thought: In this world, we must try to accomplish while knowing that one day we will be held responsible by G-d and accepting the fact that we can't know everything. He says that through this acknowledgement of the existence of G-d and the acceptance that we will never understand everything, only then can we find meaning in our lives. Then our world is completely transformed and the physical pleasures the Neheneh loves, the creativity and good that the Amal strives for, and the intellect of the Chacham can be used to find this meaning.

In class we were asked about our thoughts on this conclusion. Now that I've had some time to think about this, I'd like to share. In theory, the Yirei Elokim's beliefs sound amazing. It ties off all loose ends, considers every viewpoint, and makes a promising argument. Beautiful. But I have a few issues. We still don't have a clear "yitron" or purpose for life laid out for us. The Yirei Elokim seems to be saying that finding meaning is possible, but doesn't tell us exactly how to find this said meaning. I can't help but feel a little disappointed. Out of all the character's conclusions on life, the Yirei Elokim's is the best. But still, for me it is not good enough.

Maybe I will never be satisfied. Maybe finding meaning is a life-long pursuit. Surely it's not something that can be summed up on paper. Perhaps we won't know how to find real meaning or what that meaning looks like until it actually happens. Maybe one day it will just hit you right in the face and you'll have a moment of total clarity. Maybe meaning is something that takes it's time, dropping hints here and either until it finally all comes together. Who knows.

Sunday, December 8, 2013

You Gotta Learn Kohelet With Empathy!

So I was looking for a blog post to comment on and I came across Racheli's blog post about that they were all opinions and that they had experiences which created their opinions.

This made me think of something that we had learned in mussar: The difference between being sympathetic and empathetic.

Being sympathetic is feeling bad for someone while empathetic is actually experiencing it and feeling it with them.

In Kohelet, a lot of the times I disagree with the opinions of the Amal, Nehene, Chacham, and Y.E. Sometimes I even think that they are so ridiculous that I cannot even believe them.

In one particular instance I got really angered by the Chacham who was saying that G-d was not so extremely present in that time and he did not make miracles. I then got angered because I thought in this era G-d is rarely showing himself, even less than he did back then.

In mussar though, I realized that I do not know what it was actually like back then. I cannot be empathetic and feel how much G-d existed back then. I cannot feel the connection that the characters had with him either.

A lot of the times when I look at these philosophies and think they are crazy it is because I have never experienced them. I never really understood what Shlomo was saying through all of these character and philosophies. Okay, I learned about them and they made sense but they never made sense to ME. I always thought a lot of them were dumb and made no sense. Just like you always tell us, we have to get into the character and see it from their viewpoint. Kohelet is teaching me that it is extremely hard to understand the philosophies unless you are empathetic and actually get into character.

Why Can You be the One to Tell Us This?

With Kohelet it is different. He's not just standing up in front of you telling you his philosophies. He is telling you his life experiences. You can see all these personalities in Kohelet himself. He can tell you all of this through experience. It makes it easier to listen to him because we know he has experienced it all himself.

When Charlie Harary came to Memphis a few weeks ago, we had a Q & A session with him. We were allowed to ask him any question that we wanted to ask him and he would answer with his opinions. At first people were asking questions like why do we have to do this? Why does G-d care what we do? Then someone asked him why he has a right to tell us what to do and who to listen to?

I was very impressed by his answer. He basically answered the question with the almost the same answer that Kohelet could answer. He said the kid who asked the question was completely correct. No one had to listen to what he was saying. He was there to say what he had to say and hope people took something out of it. He was hoping that it would effect maybe one person. He said that he didn't grow up religious. He has been through it all. He knows exactly what it's like to be a teenager, but he went through a change. He went through a spiritual growth at some point and it changed his view on life completely. Yeah, we didn't have to listen to him, but he told us that he has been through it all and he knows what he is saying through experience.

Keep Calm and Break the System

In the beginning of Perek יא, the Yirei Elokim responds to the Amal. He tells him that there is a point to work, create, and prepare, even if you don't know when disaster may strike. We can't be perfect but we must act in this world, even thought we can't predict what will happen. The Yirei Elokim also tells the Amal that his previous notion that all of the nature cycles were pointless was incorrect because these cycles spread new seeds and cause new things to grow. He also adds that only G-d knows everything and only He is perfect. However, you can still do things in the world and try to make progress.

In the middle of Perek יא, the Yirei Elokim addresses the Chacham once more. He tells him that wisdom is like the sun- sometimes it will provide enlightenment and understanding, but there will also be times where it will be dark and we won't have a full understanding of what's going on. The Yirei Elokim decides that knowledge can be used for good if you recognize that you don't know everything and incomprehensibility is הבל.

Continuing on in Perek יא, we see that the Yirei Elokim finds a way to respond to all three characters in one pasuk. He tells them all that you have to participate in the world and know that you will ultimately be held accountable for your actions. The only thing man knows is that he doesn't know everything.

To the Amal, the Yirei Elokim says that people are judged positively for what you do in this world, and you can fulfill your potential. He tells the Chacham that man is limited and you must accept these limitations and then use your wisdom and knowledge to make the world a better place. He responds to the Neheneh, telling him to recognize that there is a G-d and that he'll be held accountable for his actions. Through the end of Perek יא until the beginning of Perek יב he tells the Neheneh, through a description of the decay of the human body, that he should have recognized when he was young and partying that he would die someday and his body will fail him. It will return to dust and his soul will return to G-d.

So what is the Yirei Elokim's ultimate conclusion? Unlike the rest of the characters, he actually finds meaning in life. He seems to be saying that if you recognize that there is a G-d who controls the world and will hold you accountable for your actions and you realize that you are limited in power and knowledge, then, and only then, can you find meaning. Then everything is transformed and you can use the physical (Neheneh), the creative (Amal), and the intellectual (Chacham) to find meaning in this world.

Personally, I really liked the Yirei Elokim's approach. I mean, how can you not? It's a refreshing new view, one that doesn't include too much הבל and one that actually finds meaning in life! When looking back on all of the characters and the summary of the Yirei Elokim, I found a connection to the book Divergent. If you haven't read this book yet, you're missing out and you should go buy it right away.

This book takes place (kind of like the Hunger Games) is a post-war world sometime far in the future. After a terrible world war, the rest of the human race alive came together to form a "perfect" society. The civilization is divided into 5 factions, Candor, Erudite, Dauntless, Abnegation, and Amity, each one representing the one trait that those particular people believe caused the world to fall into disarray. Each faction believed that their trait specifically was perfect.

I can see the characters of Kohelet being placed in each of these different factions: the Chacham in Erudite, where they strived for knowledge, the Neheneh in Dauntless, where they weren't afraid of anything and simply did whatever they wanted, the Amal in Candor, where they strived for ultimate honesty and perfection, and the Yirei Elokim as a Divergent, someone who broke the system. The only problem with these factions is that they were extremely strict- you had to be honest about everything, happy about everything, etc. In the end, the civilization begins to fall apart, which isn't surprising, seeing as it was built on impossibility.

Although this book isn't spot on with Kohelet, I think there are enough similarities to show us what could happen if everyone followed the views of the Amal, the Neheneh, or the Chacham. I think each of the characters in Kohelet had certain fatal flaws that completely ruined their whole ideas. The Yirei Elokim was the only one who broke the system and found a way to find a purpose.

We MUST Work Together to Achieve Success

I think that no other quote embodies Kohelet as well as this one does. When we started to learn Kohelet, we are introduced to Shlomo HaMelech in our studies of Melachim for background information. Once we delved into Kohelet itself, which is believed to be written by Shlomo, we were introduced to 4 subcounscious characters that Shlomo, himself, personisfied.

As the book goes on, we learn about each character, and what they find "hevel" in the world. We could understand this as worthless, or ephemeral. Throughout the book, each character came to their final realization, in which 3 out of the 4 of them got "were voted off the island." The fourth character gave his final speech in the last couple perakim and finally taught us what the meaning of life is. He said that the meaning of life is have a faith, and belief in a higher power.

While reading the book, I kept telling myself that all the characters would somehow come to an agreement by the end and find the meaning of life. While only one character told us the true meaning of life, I believe that there was a little bit of every character in that fourth character. The four of them represented four very important parts of life. The neheneh represented our weak spots that all of us have. We can all easily fall into a depression and just "eat, drink, and be merry," like the neheneh. Next, we had the Amal who works towards perfections. I think at times in our lives we all work towards perfection and when we can't reach it we get frustrated. The third was the chacham, who embodied wisdom, but haughty wisdom. I think that all of us have pretentious side to us in which we think that we are smarter than everyone else, and because of that we can rule the world. But, once we reach the fourth character, the Yirei Elokim, we all have that faith in G-d that we must include in our lives. No matter if you embody the neheneh, the amal, or the chacham, we ALL embody the Yirei Elokim.

Through this we can see that coming together is a beginning because it gets everyone thinking, staying together is quite hard and is progress. We saw this through the characters giving up, but lastly, they all worked together in the end to achieve success and find the meaning in life.

Just one more before we leave Kohelet...

I don't know why, but when I woke up this morning, I started thinking about the statement that "G-d helps those who help themselves." When I began thinking about that idea, I realized something. We've been talking a lot about how the mentalities of the עמל and the חכם are so prevalent in our 21st century lives, but this idea portrays something different. This idea is the exact opposite of the Amal, in that it attributes all of man's successes to G-d even when man DOES work toward it. It seems to be much more the partnership idea of the ירא א-לוקים, saying that G-d is in complete control, but man still has to take steps on his own to make something happen.

This just kinda gave me a little hope that our society isn't as self-centered and "it's-all-about-man" as it appears.

The Ultimate Purpose of Man

Anyways, the Yirei Elokim then addresses issues regarding the approach of the Amal. When we saw him last, the Amal was so terrified of imperfection that he didn't do what he had wanted to accomplish. The Yirei Elokim reassures him by acknowledging the fact that he can't be perfect; nothing will be perfect. However, he still has to act in the world, and continue to build and attempt to get rid of injustice. He also re-emphasizes the idea that the Amal cannot know everything. However, he CAN do things in the world and try to make progress.

The second issue the Yirei Elokim targets is that concerning the approach of the Chacham. He tells him that chachma can be good; it can provide enlightenment and understanding at times. But, there are also times that will be dark, when man realizes he is limited and cannot know/understand everything. However, if he accepts his limitations, he can use his wisdom to make the world a better place.

The Yirei Elokim then takes a break to collectively respond to all three characters. He urges them to participate in the world, but know that ultimately, they will be held accountable. The only thing that man knows is that he doesn't know everything.

Finally, the Yirei Elokim discusses the Neheneh. He beseeches him to recognize while he is still young, that he will die and that his body will eventually fail him. When he dies, his body will return to dust, but his soul will return to G-d. The Neheneh originally said that there was no G-d, nothing that controlled the world. The Yirei Elokim refutes him; recognize that there's a G-d and that you will be held accountable.

To summarize, the Yirei Elokim believes that if one recognizes that there's a G-d and who will hold you accountable for your actions in the world, and if you realize that you're limited in power and knowledge, then you can find meaning. Only then is everything transformed and you can use the physical (the Neheneh), the creative (the Amal), and the intellectual (Chacham) to find meaning in this world! Huzzah!

I personally like the approach of the Yirei Elokim. I think that this is how we live our lives as Jews. We recognize that we are not all-powerful. We will never be. Once we internalize that fact, we are able to find meaning in our lives. Ultimately, our purpose is to fear G-d and follow G-d's mitzvot. The problem with the first three characters was their attempt to evade that purpose, and that led them to find no meaning. The Yirei Elokim has an interesting and very realistic perspective. He tells them that their aspirations still have value. However, first they must recognize the power of G-d and that they will be judged for their actions. And then, only then, can they combine their aspirations to find this meaning they were all so desperately pursuing.

What do you think about the Yirei Elokim's approach? Do you think it satisfies/will satisfy any of the characters? If yes, how so?

Saturday, December 7, 2013

Opinions of the Kohelet Crew on Free Will

The Sefer HaChinuch said, when speaking to the victim who is now seeking revenge, that all actions are caused by G-d. Sforno said that when a sequence of actions are necessary to fulfill a Divine purpose then the actions were influenced by G-d. Rabbi Mayer Twersky said that the sinner has the ability to choose between right and wrong, but the victim should not blame the sinner because he was going to be punished anyway by G-d, whether it came from that guy or a different one.

This whole argument about man's free will got me thinking about what our favorite Kohelet characters would say about this. I could see them all having strong opinions on an issue that has to do with G-d's control versus man's control in the world and over himself. So, here's what I'm thinking about what their responses would be.

Amal: Man has complete free choice. G-d has no affect on what man chooses to do. Man has complete control Tachat HaShemesh and man should choose to fight off injustice and build the world up. Since we're going to die anyway, though, it doesn't even matter what we choose because we can't take our toils with us once we die and we can never be perfect or have everything. Basically, everything is hevel. And by hevel, I mean everything is fleeting because you can never have everything and you can't take anything you do have with you once you die.

Nehene:

Originial philosophy: Nah, man, G-d is in control. Everything comes from G-d, even our decisions. G-d created the world and is in complete control. We should enjoy what he's given us, you know. We should eat, drink, and party but anything we do is really caused by what G-d wants because He is the one in control. That's why man is not accountable for his actions. G-d controls all of our actions because He is the one in control. Since everything we do is directed by G-d and we don't have free choice, we don't have accountability either which makes us no different than animals.

Final Philosophy: Of course we have free will. I have looked at the world and I have seen mercy and judgement. Good things happening to bad people and bad things happening to good people. If both can exist in the same world, then there is chaos and anarchy so there must not be a G-d after all. If theres not G-d, then there is no afterlife and no accountability. After death, we are gone. We are not remembered and there is nothing after death. Since there's no G-d or accountability than how could there not be free choice? Nothing we choose will actually matter for anything but we definitely have the ability to choose what we want to do. It seems like the only choice we can make is to spend our lives eating, drinking, and partying. There's nothing else to live for. Life is hevel, meaning its worthless. There's nothing to live for. No G-d. No meaning. Nothing after death.

Chachum:

Original Philosophy: Yes, there is free choice, but G-d is in control. Our actions do matter. Man is not meant to be perfect and all men sin. If we can sin, then we must have the ability to choose between right and wrong. There are things that are out of our control, like the ability to be perfect. We just need to look at the reality of the situation and realize that man does sin, but he has the choice of whether or no he will.

Final Philosophy: Does man have free will? I won't even answer that question. There is no logical evidence that G-d judges man for his actions so how should I even know if man's actions matter at all? Maybe G-d controls our actions so that is why no one is judged. But that can't be true because why would G-d make such a foolish person a leader? I guess this whole system is just dumb. I should be the leader. The world is messed up. Everything is hevel-incomprehensible. If I can't understand it all, then how can I answer a question about G-d influence on our actions?!

Yirei Elokim: Man does have free will, but everything is influenced by G-d. It is a partnership. G-d has the ability to see into all the most private aspects of our lives and can control everything, but man's actions can impact the world. Man has the ability to choose between right and wrong but G-d is involved in the process. This doesn't mean everything is all about man, if it were than the nothing would have meaning. Man has the ability to choose how he will find meaning in life--through pleasure, building, or even wisdom. All he has to do is recognize G-d and that man is limited. What man chooses affects his journey through life and where his destination may be. So, man does have free choice and what he chooses can help him find meaning in life as long as he understands that he cannot know everything, man is limited, and G-d is in control. But, ultimately, man's actions will be judged and he will be held responsible for the choices he makes.

Nelson Mandela's Legacy

Friday, December 6, 2013

Why take Everything to the Extreme???

Wednesday, December 4, 2013

Neheneh + Chacham = Teen of the 21st century

Sunday, December 1, 2013

Criticizing G-d?

The חכם

In פרק ז ט-טז he brings up the issue of perfection. He responds to the עמל, who strives for only perfection, by saying that man was not made to be perfect. They were not creating in the intentions to create perfect things. You do not have control over the world, therefore how are you going to make anything perfect. In his last speech he speaks about exactly the opposite. In פרק ט the חכם creates a metaphor. One dead fly destroys a huge vat of perfume. The dead fly represents the נהנה, and the perfume represents himself. Just one small imperfection destroys a large amount of good.

The other aspect of his philosophy that stays the same throughout קוהלת is the worth of חכמב. In the beginning he explains that חכמה is the only thing that can lead you to enlightenment. There is nothing better than knowledge. Later in his philosophy he starts to become haughty about who he is. If you build a structure without architecture (wisdom), your structure will collapse. You need חכמה to guide you and help you. He also explains that you should fix your problem before it breaks. How do you do that? Only with wisdom this is possible. He even goes to the extent of saying that the leaders are corrupt because they don't have my wisdom. What the חכם needs is a little bit of manners and respect. He is too haughty and egotistical.

Fool, the insult of the century

Unfortunately this is also a problem in our world today. Each of us lives our lives in the way that we see best and the people who aren't doing what we are doing must be crazy. It may be that you are doing something right and someone else is doing something wrong but we have to look at what everyone else is doing and learn from it. Just because you think someone is doing something wrong it doesn't necessarily mean they are and it doesn't mean that you still can't learn from it.

Instead of just calling everyone a fool and not going deeper into what they have to say we and the characters of Kohelet could try to work with them to find a greater solution. If we and they acknowledge what other people have to say we might find that our opinions are not always the only ones and other people might be right.